Identify Volitional States via Intracortical BCI

My poster at SfN 2019

On October 19 - 23, 2019, I attended Society for Neuroscience (SfN) Annual meeting in Chicago, IL, USA. I presented our research with a poster, titled Identifying changes in volitional state and task engagement based on the intrinsic structure of neural ensemble activity patterns in motor cortex of people with tetraplegia during daily activities and BCI use.

You can view the poster here.

Keywords: Motor Cortex, Brain Computer Interface, tetraplegia, neural state space

Highlights

-

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are designed to bypass damaged motor pathways and provide new links to assistive technologies for people with neuromotor deficits. It is widely accepted that motor cortex incorporates a mix of incoming sensory, cognitive, and motor planning information, reflecting latent variables that are not directly related to kinematic motor output.

-

There is a need to reliably identify neural activity patterns indicative of a set of latent factors affected by task and cognitive context changes to build BCI systems that support continuous, multi-effector use.

-

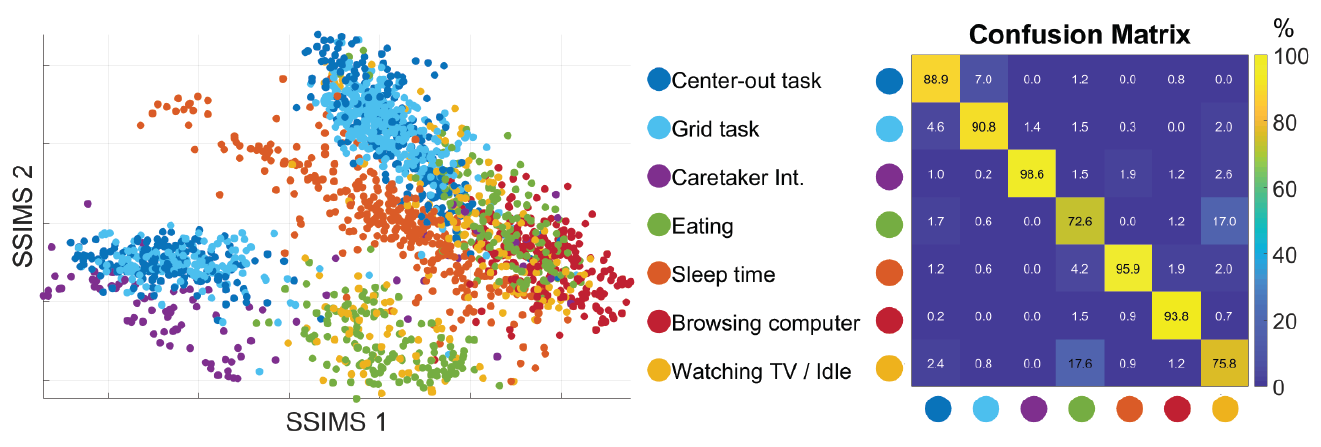

Using an approach that visualizes data by generating low-dimensional state spaces based solely on the intrinsic similarity of single unit ensemble recordings, we present the projected neural data form clusters of different context-dependent volitional states.

-

We obtain up to 80% accuracy using a K-nearest neighbor (KNN) classifier for 7 classes of daily activities recorded continuously for over a 24-hour period, and demonstrate that our approach can be used to generate state spaces that differentiate between two effectors (computer cursor vs. robotic arm) in both participants with 81.4% and 99.5% accuracy, respectively. This reflects motor cortex encodes useful information about volitional states, in addition to precise intended movements.

Introduction

Neuromotor deficits resulting from conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), brainstem stroke, and spinal cord injury (SCI) result in loss of volitional movement reducing independence. Brain-computer interfaces (BCI) bypass damaged motor pathways and provide new links to assistive technologies. Voluntary action engages vast networks of neurons performing complex calculations which are still not fully understood. It is widely accepted that motor cortex incorporates a mix of incoming sensory, cognitive, and motor planning information, reflecting latent variables that are not directly related to kinematic motor output. Reliably identifying neural activity patterns indicative of a set of latent factors impacted by task and cognitive context is a challenge for developing BCI systems that support continuous, multi-effector use.

Studies previously showed successful decoding of contextual changes in idle vs. active states 1, and controlling different end effectors 2. Here we present a new approach to generate state spaces based solely on the intrinsic properties of single unit ensemble recordings. We used Spike train SIMilarity Space (SSIMS) analysis to map neural activity patterns into low dimensional state spaces. These state space projections can be used to identify clusters of similar, recurring activity patterns, without the need to define task-related tuning models for individual neurons.

Methods

Participants and Implants

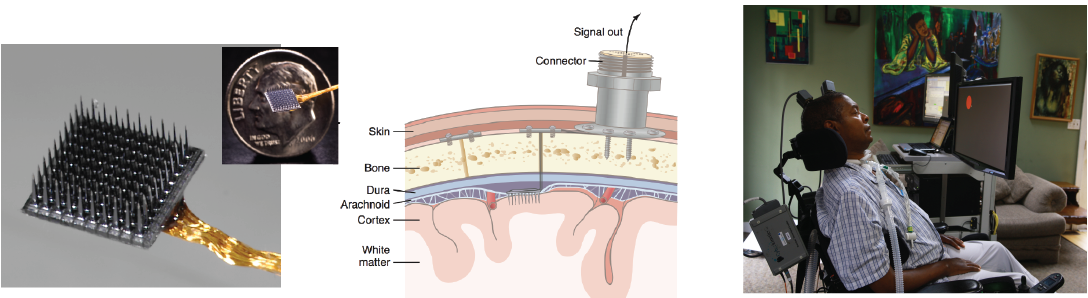

Data are collected from two participants enrolled in the pilot clinical trial (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00912041) of the BrainGate2 Neural Interface System - T9 is a 52-year-old (at the start of the study) man with tetraplegia due to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALSFRS-R of 8), and T10 is a 35-year-old man with tetraplegia due to spinal cord injury (C4 AIS-A). Two 96-channel Utah microelectrode arrays (Blackrock Microsystem, Inc.) were placed on the left precentral gyrus (PCG) - the dominant hand/arm knob area of motor cortex3 - for T9, and one array was placed on the left middle frontal gyrus (MFG) and one on the left PCG for T10.

Data Acquisition

Raw neural signals for each electrode were sampled at 30 kHz using the NeuroPort System (Blackrock Microsystems,Salt Lake City, UT). Then they are processed using the xPC target real-time operating system (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Raw signals were further down sampled to 15 kHz then denoised by subtracting an instantaneous common average reference using 40 of the 96 channels on each array with the lowest root-mean-square (rms) value, identified during a “reference block” at the beginning of each session. The denoised signals were non-causally bandpass-filtered between 250Hz and 5000Hz using an eighth-order Butterworth filter4. Spike events were defined by crossing a threshold set at 3.5 x rms amplitude of each channel, as determined by data from a 1-minute reference block at the start of each research session. The rate of threshold crossings in 20 ms bins(not spike-sorted) on each channel were extracted as one of the neural features.

Spike Train SIMilarity Space (SSIMS)

We used Spike train SIMilarity Space (SSIMS) analysis to map neural activity patterns into low dimensional state spaces5. It is a two-step process. First, we compute a matrix that measures the similarity metric between pairs of spike trains by calculating the cost to transform one spike train to another with inserting, deleting, or shifting spikes 6. Then, we perform dimensionality reduction using t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding7, which enable us to visualize the state space in a 3D plane.

These state space projections can be used to identify clusters of similar, recurring activity patterns, solely based on the intrinsic structure of neural ensemble activity patterns, eliminating the need to define task-related tuning models for individual neurons.

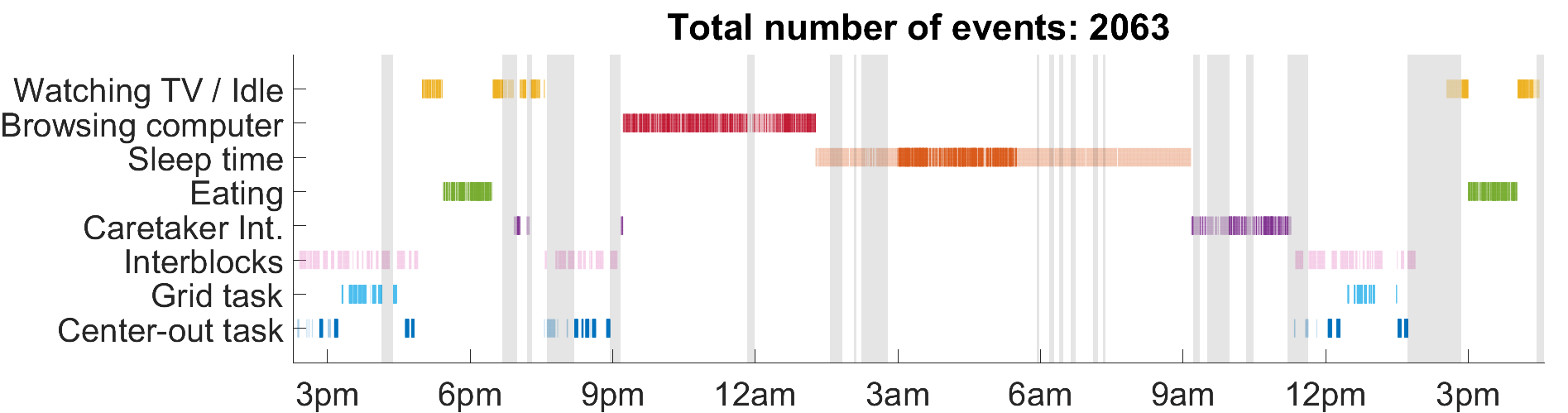

I. Full day continuous neural recording of BCI use and daily activities

We recorded data from participant T10 over a 24-hour period. Our findings suggest that state space models based on neurons ensemble intrinsic similarity can be used to detect context-dependent changes in volitional state, providing a useful indicator of when BCI control modes should be adjusted. Span across two days, this 26-hour continuous recordings was obtained via a wireless neural interface8\(^,\)9\(^,\)10. T10 was engaging in BCI use and other usual daily activities, such as watching TV, sleeping, eating, browsing with his computer and interacting with his caretaker.

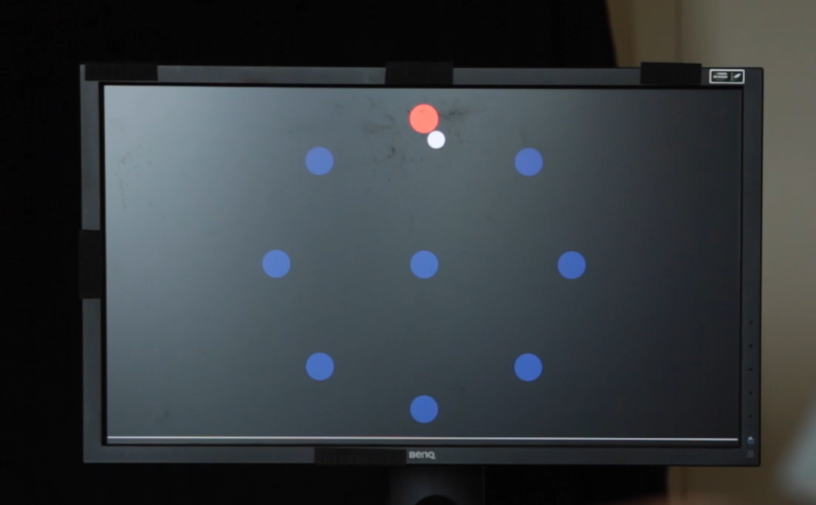

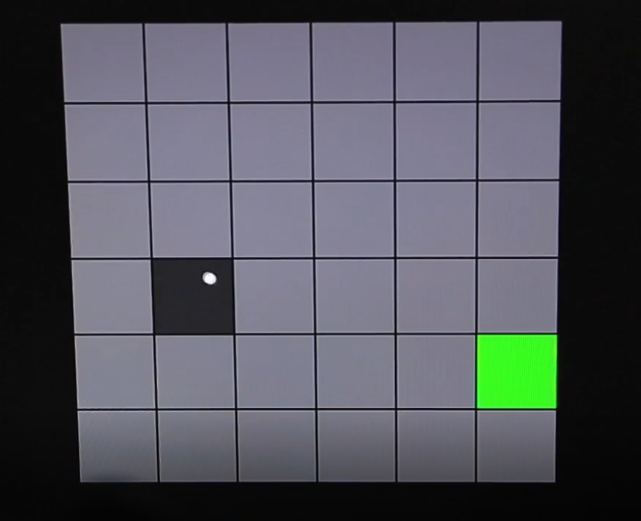

In both days, T10 performed two types of BCI tasks: radial-8 task and grid task. In radial-8 task, targets were presented alternating between one of eight radially distributed targets and a center target in a pseudo-random order. In grid task, targets were presented in a sequential pseudo-randomly order.

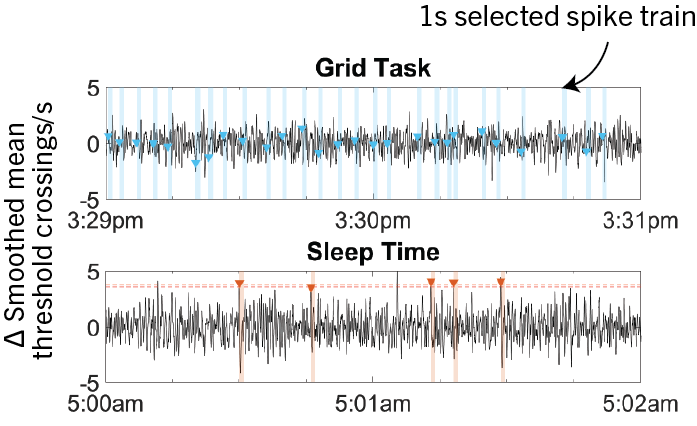

Data Selection

Since SSIMS can get computationally expensive as number of spike trains increases, we sampled a selection of spike trains that represent each categories. Each “event” denotes a one-second long spike train. For BCI tasks, we selected events one second after the ‘go’ cue in each trial of the tasks. For other categories, events in top percentile of change in smoothed mean threshold crossings after outlier elimination (to avoid signal dropout and electronic noise) were chosen. For sleeping, we performed a spectral analysis and determined the period when T10 was in deep sleep. Events were only picked within this period. A total of 2063 events were selected.

Results

We plotted the SSIMS space as shown above. We observed that sleeping events form a cluster far from the rest of the categories, and browsing with his computer and interacting with caretaker also form two distinctive clusters. What the SSIMS plot reflects is that events of the same type of categories give rise to similar and recurring activity patterns, which appear close to each other in identifiable clusters.

Interestingly, the two BCI tasks interweave but were also separated into two clusters. The two clusters actually corresponded to events from the two consecutive days respectively. They interweaves possibly because the two BCI tasks were much more similar to each other than the rest of the categories. Similarly, eating and watching TV also interweaves with each other, and form two clusters that also corresponded to the two consecutive days. They were interweave possibly because T10 was watching TV when eating.

With a 10-fold cross validated 5-Nearest-Neighbor (KNN) of the seven states, we achieved 81.18% ± 2.38% accuracy, well above chance (17.82%). The confusion matrix of the KNN also confirmed our previous observation from the 3D plot: eating and watching TV are much likely to be misclassified, followed by the two BCI tasks. Other categories have high accurate up to 90%.

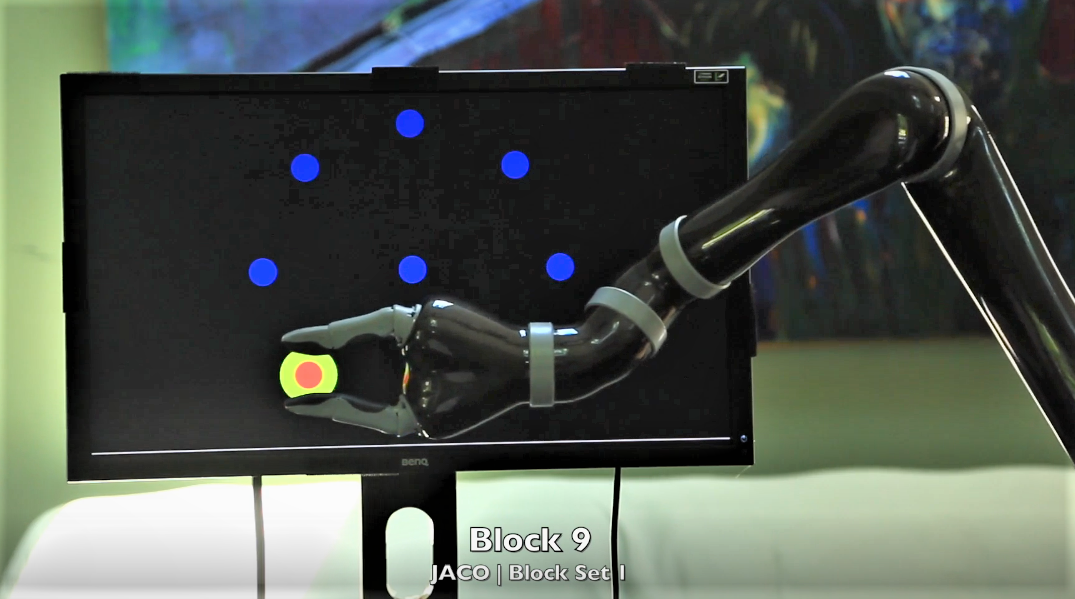

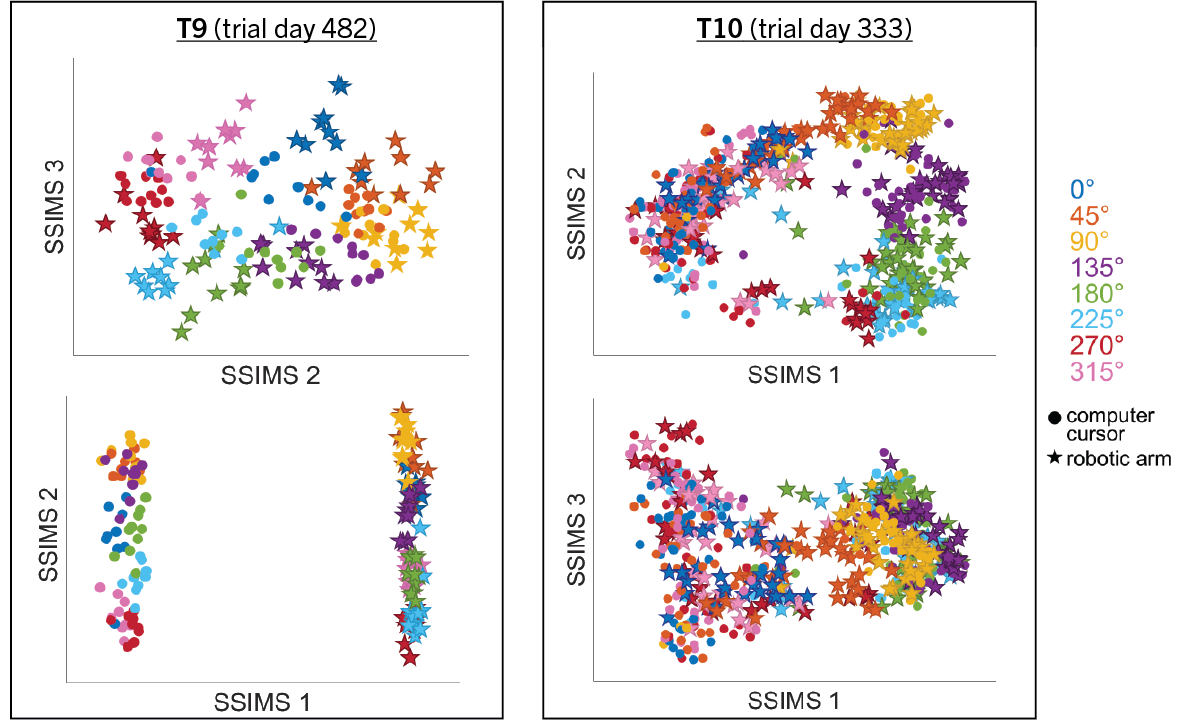

II. Cursor vs Robotic Arm

We hypothesized that the neural ensemble encoding is significantly different as the iBCI user attempt to control different effector mediums. As part of the BrainGate2 pilot clinical trial, two participants were asked to control either a computer cursor or a JACO robotic arm (Kinova Robotics, Montreal, Canada) during the same two-dimensional target acquisition tasks via iBCI. The JACO robotic arm was constrained to two dimensions only by placing its hand 4 inches in front of the computer screen where the tasks were presented.

In each recording session (eight sessions for T9 and four for T10), the decoder was first calibrated using open-loop imagery where the participant observed and imagined either single effector movement or simultaneous cursor and robotic arm movement. Then the participant engaged in closed-loop control on alternating blocks between the two effectors. One day of research “session” consists of multiple “blocks” of discrete recording epochs that usually last for several minutes. A block consists of many trials of the same task. In our session, a trial is to acquire a cued target without instruction delay.

Data Selection

Since we recorded the timing of the presented cues and target acquisitions, we can extract the neural data correspond to the trials. We took 2.5 second long of spike train before target is acquired.

Results

We demonstrate that our approach can be used to generate state spaces that highlights the similarities and differences in neural activity when engaging in different end-effectors control. As shown in the 3D plots below, we can conclude that engaging different effectors does elicits different neural activity patterns. This contextual difference can be used to differentiate between effectors (cursor vs. robotic arm) in both participants.

For the above session of T9, we can observed a separation between effectors (marker shapes) in one perspective. Interestingly, of the same 3D plot, we can also see a circular clusters of target directions (marker colors) that resembles the peripheral targets in the radial-8 task. State space representations in other sessions of T9 also look similar to the above space. For T10, there was a less clear separation between effectors than T9, but directional clusterings can still be observed in general.

Using a 10-fold cross validated KNN (K=3) averaged across all sessions, we obtained:

- direction classification - T9 : 63.52 ± 9.20% and T10 : 43.57 ± 7.63%

- effector classification - T9 : 97.58 ± 1.55% and T10 : 87.94 ± 5.17%

Conclusion and Future Work

State space analysis based on intrinsic activity pattern similarity can be useful to: (1) detect context-dependent changes in volitional state across daily activities (2) differentiate between the intention to engage different effectors (cursor vs. robot arm)

These results indicates motor cortex contains information about volitional states and employ separate neural encoding paradigms when attempting to use different effector mediums to perform similar tasks, in addition to information about intended movements.

These findings have potential long-range implications for effective 24/7 iBCI control of assistive technologies in varied contexts by individuals with tetraplegia.

Future work includes comparing various dimensionality reduction techniques, investigating non-stationarity across days, obtaining more than one day of continuous data, using these data to support the development of a highly interactive BCI system that enables continuous, multi-effector use for people with tetraplegia.

This study was performed with approval of the Institutional Review Boards of Brown University and Partners Healthcare/Massachusetts General Hospital under an investigational device exemption from the United States Food and Drug Administration. It is supported by Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation R&D Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, NIH and Massachusetts General Hospital.

-

Lesenfants D, Saab J, Brandman DM, Jarosiewicz B, Sorice B, Sarma AA, Simeral JD, Donoghue JP, Hochberg LR. (2015). User state-based modulation of intracortical activity: distinguishing the idle state. Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Chicago, IL: Society for Neuroscience, 2015. Online. ↩

-

Fasoli S, Chavakula V, Brandman D, Vargas-Irwin C, Saab J, Hosman T, Franco B, Simeral J,Donoghue J, Hochberg L. (2017). Intracortical brain-computer interface (iBCI) to control multiple end effectors: effects of context. Abstract ID 305174. American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine 94th Annual Conference, Progress in Rehabilitation Medicine. Atlanta, GA. ↩

-

Yousry T. A., Schmid, U. D., Alkadhi, H., Schmidt, D., Peraud, A., Buettner, A., & Winkler, P. (1997). Localization of the motor hand area to a knob on the precentral gyrus. A new landmark. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 120 ( Pt 1), 141–157. ↩

-

Masse, N. Y., Jarosiewicz, B., Simeral, J. D., Bacher, D., Stavisky, S. D., Cash, S. S., Oakley, E. M., Berhanu, E., Eskandar, E., Friehs, G., Hochberg, L. R., & Donoghue, J. P. (2014). Non-causal spike filtering improves decoding of movement intention for intracortical BCIs. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 236, 58–67. ↩

-

Vargas-Irwin, C. E., Brandman, D. M., Zimmermann, J. B., Donoghue, J. P., & Black, M. J. (2015). Spike train SIMilarity Space (SSIMS): a framework for single neuron and ensemble data analysis. Neural Computation, 27(1), 1–31. ↩

-

Victor, J. D., & Purpura, K. P. (1996). Nature and precision of temporal coding invisual cortex: A metric-space analysis. J. Neurophysiol., 76(2), 1310–1326. ↩

-

Maaten, L. van der, & Hinton, G. (2008). Visualizing Data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 9, 2579–2605. ↩

-

Borton DA, Yin M, Aceros J, Nurmikko A. (2013). An implantable wireless neural interface for recording cortical circuit dynamics in moving primates. J Neural Eng. 10(2), 026010. ↩

-

Saab J, Hosman T, Yin M, Borton DA, Franco B, Kelemen J, Brandman DM, Vilela M, Ciancibello JG, Larson L, Rosler DM, Simeral JD, Nurmikko AV, Hochberg LR. (2017). Wireless intracortical BCI cursor control by a person with tetraplegia. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience, 2017. Online. ↩

-

Simeral, J. D., Hosman, T., Saab, J., Flesher, S. N., Vilela, M., Franco, B., Kelemen, J., Brandman, D. M., Ciancibello, J. G., Rezaii, P. G., Rosler, D. M., Shenoy, K. V., Henderson, J. M., Nurmikko, A. V., & Hochberg, L. R. (2019). Home Use of a Wireless Intracortical Brain-Computer Interface by Individuals With Tetraplegia. In Neurology (No. medrxiv;2019.12.27.19015727v1). medRxiv. ↩